A Structured Self-attentive Sentence Embedding¶

After the novelty of word embeddings to create new numerical representations of words, natural language processing (NLP) has still been effectively improved in many ways. Along with the widespread use of embedding techniques, many other methods have been developed to further express the semantics and meanings of sentences with words:

A vector representation of multiple words in a sentence can be concatenated or weighted to obtain a vector to represent the entirety of a sentence.

Convolution (CNN) and maximum pooling (MaxPooling) on the matrix of all the word vectors of the sentence, using the final result of these techniques to represent the sentence as a whole.

Unrolling the sentence according to the time step of the word, inputting the vector representation of each word into a recurrent neural network (RNN), and using the output of the last time step of the RNN as the representation of the sentence.

The above methods solve the problem of sentence meaning, but only to a certain extent. When concatenating is used in method one, if the word of the sentence is too long and the vector dimension of the word is slightly larger, then the vector dimension of the sentence will be particularly large, and the internal interaction between the words of the sentence can not be taken into account. The use of weighted averaging is not accurate and does not adequately express the impact of each word on sentence semantics.

In the second method, many useful word meanings may be lost using CNNs and MaxPooling.

In the third method, the representation selected is only the output of the last step. If a sentence is too long, the output of the last step does not accurately express the entirety of the sentence’s semantics.

Based on the aforementioned method, Zhouhan Lin, Minwei Feng et al. published a paper A Structured Self-attentive Sentence Embedding[1] in 2017, proposing a novel method based on self-attention structures for sentence embedding and application to users’ review classification, textual entailment and other NLP tasks. In the end, better results were obtained than the previous methods.

In this tutorial, we will use GluonNLP to reproduce the model structure in “A Structured Self-attentive Sentence Embedding” and apply it to Yelp Data’s review star rating data set for classification.

Importing necessary packages¶

The first step, as in every one of these tutorials, is to import the necessary packages.

In [1]:

import os

import json

import zipfile

import time

import itertools

import numpy as np

import mxnet as mx

import multiprocessing as mp

import gluonnlp as nlp

from mxnet import gluon, nd, init

from mxnet.gluon import nn, rnn

from mxnet import autograd, gluon, nd

# iUse sklearn's metric function to evaluate the results of the experiment

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, f1_score

# fixed random number seed

np.random.seed(2018)

mx.random.seed(2018)

def try_gpu():

"""If GPU is available, return mx.gpu(0); else return mx.cpu()."""

try:

ctx = mx.gpu()

_ = nd.array([0], ctx=ctx)

except:

ctx = mx.cpu()

return ctx

Data pipeline¶

The next step is to load and format the data according to the requirements of our model. The dataset used in this tutorial is the Yelp users’ review dataset.

Loading the dataset¶

The Yelp users’ review dataset is formatted as a JSON. The original paper selected 500,000 documents as the training set, 2,000 as the validation set, and 2,000 as the test set. For easier reproducibility of the experiment, we subsampled 198,000 documents from this dataset as the training set and 2,000 documents as validation set.

Each sample in the data consists of a user’s comment, in English, with each comment marked one through five, each number representing one of five different emotions the user expressed. Here we download, unzip, and reformat the dataset for ease of use further on.

In [2]:

# Download the data from the server

data_url = 'http://apache-mxnet.s3-accelerate.dualstack.amazonaws.com/gluon/dataset/yelp_review_subset-167bb781.zip'

zip_path = mx.gluon.utils.download(data_url)

# Unzip the zip file

zip_file = zipfile.ZipFile(zip_path)

json_path = zip_file.extract(zip_file.namelist()[0])

## Load the JSON data

with open(json_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as fr:

data = json.load(fr)

# Create a list of review a label pairs

dataset = [[text, int(label)] for text, label in zip(data['texts'], data['labels'])]

# Randomly divide one percent from the training set as a verification set

train_dataset, valid_dataset = nlp.data.train_valid_split(dataset, 0.01)

len(train_dataset), len(valid_dataset)

Downloading yelp_review_subset-167bb781.zip from http://apache-mxnet.s3-accelerate.dualstack.amazonaws.com/gluon/dataset/yelp_review_subset-167bb781.zip...

Out[2]:

(198000, 2000)

Preliminary processing of the data¶

The purpose of the following code is to process the raw data so that the

pre-processed data can be used for model training and prediction. We

will use the SpacyTokenizer to split the document into tokens,

ClipSequence to crop the comments to the specified length, and then

build a vocabulary based on the word frequency of the training data.

Next, we attach the Glove

[2] pre-trained word vector to the vocabulary and convert each token

into the corresponding word index in the vocabulary. Finally, we get the

standardized training data set and verification data set. Here we also

define a few helper functions for later. We take advantage of the

mp.Pool() function to spread the pre-processing over multiple cores

or machines.

In [3]:

# The tokenizer takes as input a string and outputs a list of tokens.

tokenizer = nlp.data.SpacyTokenizer('en')

# `length_clip` takes as input a list and outputs a list with maximum length 100.

length_clip = nlp.data.ClipSequence(100)

def preprocess(x):

# Convert the number of stars 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 to zero-based index, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

data, label = x[0], x[1]-1

# Clip the length of review words

data = length_clip(tokenizer(data))

return data, label

def get_length(x):

return float(len(x[0]))

def preprocess_dataset(dataset):

start = time.time()

with mp.Pool() as pool:

# Each sample is processed in an asynchronous manner.

dataset = gluon.data.SimpleDataset(pool.map(preprocess, dataset))

lengths = gluon.data.SimpleDataset(pool.map(get_length, dataset))

end = time.time()

print('Done! Tokenizing Time={:.2f}s, #Sentences={}'.format(end - start, len(dataset)))

return dataset, lengths

# Preprocess the dataset

train_dataset, train_data_lengths = preprocess_dataset(train_dataset)

valid_dataset, valid_data_lengths = preprocess_dataset(valid_dataset)

Done! Tokenizing Time=26.34s, #Sentences=198000

Done! Tokenizing Time=0.63s, #Sentences=2000

This section creates the vocab object and converts the dataset’s

words to the Glove embeddings.

In [4]:

# Create the vocab

train_seqs = [sample[0] for sample in train_dataset]

counter = nlp.data.count_tokens(list(itertools.chain.from_iterable(train_seqs)))

vocab = nlp.Vocab(counter, max_size=10000)

# Load the pre-trained embedding, in this case the Glove embedding of 300 dimensions

embedding_weights = nlp.embedding.GloVe(source='glove.6B.300d')

vocab.set_embedding(embedding_weights)

print(vocab)

def token_to_idx(x):

return vocab[x[0]], x[1]

# A token index or a list of token indices is returned according to the vocabulary.

with mp.Pool() as pool:

train_dataset = pool.map(token_to_idx, train_dataset)

valid_dataset = pool.map(token_to_idx, valid_dataset)

Embedding file glove.6B.300d.npz is not found. Downloading from Gluon Repository. This may take some time.

Downloading /root/.mxnet/embedding/glove/glove.6B.300d.npz from https://apache-mxnet.s3-accelerate.dualstack.amazonaws.com/gluon/embeddings/glove/glove.6B.300d.npz...

Vocab(size=10004, unk="<unk>", reserved="['<bos>', '<pad>', '<eos>']")

Bucketing, mini-batches, and the DataLoader¶

Since each sentence may have a different length, we need to use Pad

to fill the sentences in a mini-batch to equal lengths so that the data

can be quickly tensored on the GPU. At the same time, we need to use

Stack to stack the category tags of a batch of data. For

convenience, we use Tuple to combine Pad and Stack.

In order to make the length of the sentence pad in each mini-batch as

small as possible, we should make the sentences with similar lengths in

a batch as much as possible. In light of this, we consider constructing

a sampler using FixedBucketSampler, which defines how the samples in

a dataset will be iterated in a more economical way.

Finally, we use DataLoader to build a data loader for the training

and validation datasets. The training dataset requires a

FixedBucketSampler, but the validation dataset doesn’t require the

sampler.

Here we define the helper functions to do all of the above as well as define the hyperparameters for this section:

In [5]:

batch_size = 64

bucket_num = 10

bucket_ratio = 0.5

def get_dataloader():

# Construct the DataLoader Pad data, stack label and lengths

batchify_fn = nlp.data.batchify.Tuple(

nlp.data.batchify.Pad(axis=0, pad_val=0),

nlp.data.batchify.Stack())

# In this example, we use a FixedBucketSampler,

# which assigns each data sample to a fixed bucket based on its length.

batch_sampler = nlp.data.sampler.FixedBucketSampler(

train_data_lengths,

batch_size=batch_size,

num_buckets=bucket_num,

ratio=bucket_ratio,

shuffle=True)

print(batch_sampler.stats())

# Training set DataLoader

train_dataloader = gluon.data.DataLoader(

dataset=train_dataset,

batch_sampler=batch_sampler,

batchify_fn=batchify_fn)

# Validation set DataLoader

valid_dataloader = gluon.data.DataLoader(

dataset=valid_dataset,

batch_size=batch_size,

shuffle=False,

batchify_fn=batchify_fn)

return train_dataloader, valid_dataloader

train_dataloader, valid_dataloader = get_dataloader()

FixedBucketSampler:

sample_num=198000, batch_num=2922

key=[10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100]

cnt=[269, 4489, 13825, 14963, 14998, 14055, 12909, 11664, 10275, 100553]

batch_size=[320, 160, 106, 80, 64, 64, 64, 64, 64, 64]

Constructing the model and outlining the model’s structure¶

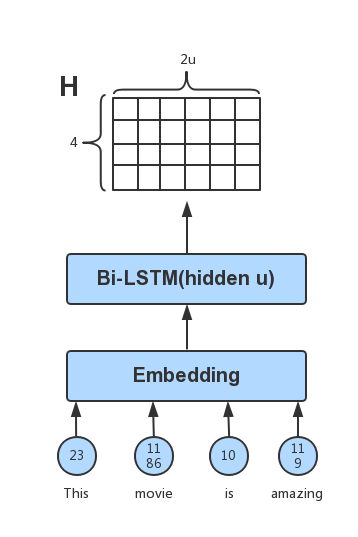

In the original paper, the representation of the sentence is broken into the following steps:

Firstly, the sentence is disassembled into a list corresponding to the

word. Then the words are unrolled in order, and the word vector of each

word is calculated as the input of each step of the bidirectional LSTM

neural network

layer [3].

Taking the output of each step of the bidirectional LSTM network layer,

a matrix H is obtained. Suppose the hidden_dim of the bidirectional

LSTM is U, the word length of the sentence is N, then the

dimension of the last H is N x 2U. For example, the sentence “This

movie is amazing!” would be represented as:

Attention is very similar to when we are actually looking at an object, we always give different importance (or weights) to things in the scope of the perspective. A brief quote from skymind.ai summarizes what attention means in our daily lives as well as in neural networks in a few clear words:

The word describes the mind’s ability to allocate consideration unevenly across a field of sensation, thought and proprioception, to focus and bring certain inputs to the fore, while ignoring or diminishing the importance of others. So for neural networks, we’re basically talking about credit assignment. [4]

For example, when we are communicating with people, our eyes will always

pay more attention to the face of the communicator, rather than the type

of trousers they are wearing or their toe nail polish. So when we are

expressing a sentence with this model, we can pay different amounts of

attention to the output H of the bi-directional LSTM layer.

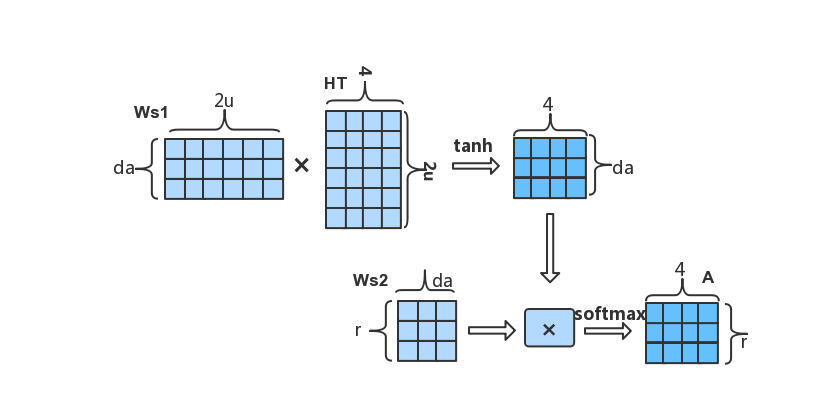

Here, Ws1 is a weight matrix with the shape: da-by-2u, where da is a hyperparameter. Ws2 is a weight matrix with the shape: r-by-da, where r is the number of different attentions you want to use.

When the attention matrix A and the output H of the LSTM are

obtained, the final representation is obtained by

.

We can first customize a layer of attention, specify the number of

hidden nodes (att_unit) and the number of attention channels

(att_hops).

In [6]:

# A custom attention layer

class SelfAttention(nn.HybridBlock):

def __init__(self, att_unit, att_hops, **kwargs):

super(SelfAttention, self).__init__(**kwargs)

with self.name_scope():

self.ut_dense = nn.Dense(att_unit, activation='tanh', flatten=False)

self.et_dense = nn.Dense(att_hops, activation=None, flatten=False)

def hybrid_forward(self, F, x):

# x shape: [batch_size, seq_len, embedding_width]

# ut shape: [batch_size, seq_len, att_unit]

ut = self.ut_dense(x)

# et shape: [batch_size, seq_len, att_hops]

et = self.et_dense(ut)

# att shape: [batch_size, att_hops, seq_len]

att = F.softmax(F.transpose(et, axes=(0, 2, 1)), axis=-1)

# output shape [batch_size, att_hops, embedding_width]

output = F.batch_dot(att, x)

return output, att

When the number of samples for labels are very unbalanced, applying different weights on different labels may improve the performance of the model significantly.

In [7]:

class WeightedSoftmaxCE(nn.Block):

def __init__(self, sparse_label=True, from_logits=False, **kwargs):

super(WeightedSoftmaxCE, self).__init__(**kwargs)

with self.name_scope():

self.sparse_label = sparse_label

self.from_logits = from_logits

def forward(self, pred, label, class_weight, depth=None):

if self.sparse_label:

label = nd.reshape(label, shape=(-1, ))

label = nd.one_hot(label, depth)

if not self.from_logits:

pred = nd.log_softmax(pred, -1)

weight_label = nd.broadcast_mul(label, class_weight)

loss = -nd.sum(pred * weight_label, axis=-1)

# return nd.mean(loss, axis=0, exclude=True)

return loss

We now define the basic model characteristics in a self-attentive bi-LSTM model, and configure the layers and dropout, as well as how the model feeds forward.

In [8]:

class SelfAttentiveBiLSTM(nn.HybridBlock):

def __init__(self, vocab_len, embsize, nhidden, nlayers, natt_unit, natt_hops, nfc, nclass,

drop_prob, pool_way, prune_p=None, prune_q=None, **kwargs):

super(SelfAttentiveBiLSTM, self).__init__(**kwargs)

with self.name_scope():

self.embedding_layer = nn.Embedding(vocab_len, embsize)

self.bilstm = rnn.LSTM(nhidden, num_layers=nlayers, dropout=drop_prob, bidirectional=True)

self.att_encoder = SelfAttention(natt_unit, natt_hops)

self.dense = nn.Dense(nfc, activation='tanh')

self.output_layer = nn.Dense(nclass)

self.dense_p, self.dense_q = None, None

if all([prune_p, prune_q]):

self.dense_p = nn.Dense(prune_p, activation='tanh', flatten=False)

self.dense_q = nn.Dense(prune_q, activation='tanh', flatten=False)

self.drop_prob = drop_prob

self.pool_way = pool_way

def hybrid_forward(self, F, inp):

# input_embed: [batch, len, emsize]

inp_embed = self.embedding_layer(inp)

h_output = self.bilstm(F.transpose(inp_embed, axes=(1, 0, 2)))

# att_output: [batch, att_hops, emsize]

att_output, att = self.att_encoder(F.transpose(h_output, axes=(1, 0, 2)))

dense_input = None

if self.pool_way == 'flatten':

dense_input = F.Dropout(F.flatten(att_output), self.drop_prob)

elif self.pool_way == 'mean':

dense_input = F.Dropout(F.mean(att_output, axis=1), self.drop_prob)

elif self.pool_way == 'prune' and all([self.dense_p, self.dense_q]):

# p_section: [batch, att_hops, prune_p]

p_section = self.dense_p(att_output)

# q_section: [batch, emsize, prune_q]

q_section = self.dense_q(F.transpose(att_output, axes=(0, 2, 1)))

dense_input = F.Dropout(F.concat(F.flatten(p_section), F.flatten(q_section), dim=-1), self.drop_prob)

dense_out = self.dense(dense_input)

output = self.output_layer(F.Dropout(dense_out, self.drop_prob))

return output, att

Configuring the parameters and assembling the model¶

The resulting M is a matrix, and the way to classify this matrix is

flatten-ing, mean-ing or prune-ing. Pruning is an effective

way of trimming parameters that was proposed in the original paper, and

has been implemented for our example.

In [9]:

vocab_len = len(vocab)

emsize = 300 # word embedding size

nhidden = 300 # lstm hidden_dim

nlayers = 2 # lstm layers

natt_unit = 300 # the hidden_units of attention layer

natt_hops = 2 # the channels of attention

nfc = 512

nclass = 5

drop_prob = 0.5

pool_way = 'flatten' # The way to handle M

prune_p = None

prune_q = None

ctx = try_gpu()

model = SelfAttentiveBiLSTM(vocab_len, emsize, nhidden, nlayers,

natt_unit, natt_hops, nfc, nclass,

drop_prob, pool_way, prune_p, prune_q)

model.initialize(init=init.Xavier(), ctx=ctx)

model.hybridize()

# Attach a pre-trained glove word vector to the embedding layer

model.embedding_layer.weight.set_data(vocab.embedding.idx_to_vec)

# fixed the layer

model.embedding_layer.collect_params().setattr('grad_req', 'null')

Using r attention can improve the representation of sentences with

different semantics, but if the value of each line in the attention

matrix A (r-byn) is very close, that is, there is no difference

between several attentions. Subsequently, in

, the resulting M will contain a lot of redundant information. So in

order to solve this problem, we should try to force A to ensure that

the value of each line has obvious differences, that is, try to satisfy

the diversity of attention. Therefore, a penalty can be used to achieve

this goal.

It can be seen from the above formula that if the value of each row of

A is more similar, the result of P will be larger, and the value

of A is less similar for each row, and P is smaller. This means

that when the r-focused diversity of A is larger, the smaller P

is. So by including this penalty item with the loss of the model, we can

try to ensure the diversity of A.

We incorporate these findings in the code below adding in the penalty coefficient along with the standard loss function.

In [10]:

def calculate_loss(x, y, model, loss, class_weight, penal_coeff):

pred, att = model(x)

if loss_name == 'sce':

l = loss(pred, y)

elif loss_name == 'wsce':

l = loss(pred, y, class_weight, class_weight.shape[0])

# penalty

diversity_penalty = nd.batch_dot(att, nd.transpose(att, axes=(0, 2, 1))

) - nd.eye(att.shape[1], ctx=att.context)

l = l + penal_coeff * diversity_penalty.norm(axis=(1, 2))

return pred, l

We then define what one epoch of training would be for the model for

easier use later. In addition, we calculate loss, the F1 score, and

accuracy for each epoch and print them for easier understanding.

Additionally, we dynamically adjust the learning rate as the number of

epochs increase. We also include an is_train boolean to allow us to

know whether or not we should be altering the original model or just

reporting the loss.

In [11]:

def one_epoch(data_iter, model, loss, trainer, ctx, is_train, epoch,

penal_coeff=0.0, clip=None, class_weight=None, loss_name='wsce'):

loss_val = 0.

total_pred = []

total_true = []

n_batch = 0

for batch_x, batch_y in data_iter:

batch_x = batch_x.as_in_context(ctx)

batch_y = batch_y.as_in_context(ctx)

if is_train:

with autograd.record():

batch_pred, l = calculate_loss(batch_x, batch_y, model, loss, class_weight, penal_coeff)

# backward calculate

l.backward()

# clip gradient

clip_params = [p.data() for p in model.collect_params().values()]

if clip is not None:

norm = nd.array([0.0], ctx)

for param in clip_params:

if param.grad is not None:

norm += (param.grad ** 2).sum()

norm = norm.sqrt().asscalar()

if norm > clip:

for param in clip_params:

if param.grad is not None:

param.grad[:] *= clip / norm

# update parmas

trainer.step(batch_x.shape[0])

else:

batch_pred, l = calculate_loss(batch_x, batch_y, model, loss, class_weight, penal_coeff)

# keep result for metric

batch_pred = nd.argmax(nd.softmax(batch_pred, axis=1), axis=1).asnumpy()

batch_true = np.reshape(batch_y.asnumpy(), (-1, ))

total_pred.extend(batch_pred.tolist())

total_true.extend(batch_true.tolist())

batch_loss = l.mean().asscalar()

n_batch += 1

loss_val += batch_loss

# check the result of traing phase

if is_train and n_batch % 400 == 0:

print('epoch %d, batch %d, batch_train_loss %.4f, batch_train_acc %.3f' %

(epoch, n_batch, batch_loss, accuracy_score(batch_true, batch_pred)))

# metric

F1 = f1_score(np.array(total_true), np.array(total_pred), average='weighted')

acc = accuracy_score(np.array(total_true), np.array(total_pred))

loss_val /= n_batch

if is_train:

print('epoch %d, learning_rate %.5f \n\t train_loss %.4f, acc_train %.3f, F1_train %.3f, ' %

(epoch, trainer.learning_rate, loss_val, acc, F1))

# declay lr

if epoch % 2 == 0:

trainer.set_learning_rate(trainer.learning_rate * 0.9)

else:

print('\t valid_loss %.4f, acc_valid %.3f, F1_valid %.3f, ' % (loss_val, acc, F1))

In addition, we include a helper method train_valid which combines

the one epoch for the training data as well as the validation data,

using the is_train boolean to swap between the two modes we

discussed above.

In [12]:

def train_valid(data_iter_train, data_iter_valid, model, loss, trainer, ctx, nepochs,

penal_coeff=0.0, clip=None, class_weight=None, loss_name='wsce'):

for epoch in range(1, nepochs+1):

start = time.time()

# train

is_train = True

one_epoch(data_iter_train, model, loss, trainer, ctx, is_train,

epoch, penal_coeff, clip, class_weight, loss_name)

# valid

is_train = False

one_epoch(data_iter_valid, model, loss, trainer, ctx, is_train,

epoch, penal_coeff, clip, class_weight, loss_name)

end = time.time()

print('time %.2f sec' % (end-start))

print("*"*100)

Training the model¶

Now that we are actually training the model, we use

WeightedSoftmaxCE to alleviate the problem of data categorical

imbalance. We perform statistical analysis on the data in advance to

retrieve a set of class_weights.

In [13]:

class_weight = None

loss_name = 'wsce'

optim = 'adam'

lr = 0.001

penal_coeff = 0.1

clip = 0.5

nepochs = 4

trainer = gluon.Trainer(model.collect_params(), optim, {'learning_rate': lr})

if loss_name == 'sce':

loss = gluon.loss.SoftmaxCrossEntropyLoss()

elif loss_name == 'wsce':

loss = WeightedSoftmaxCE()

# the value of class_weight is obtained by counting data in advance. It can be seen as a hyperparameter.

class_weight = nd.array([3.0, 5.3, 4.0, 2.0, 1.0], ctx=ctx)

We’ve simplified our lives earlier by creating the necessary helper methods so our training is as simple as the below line of code.

In [14]:

# train and valid

train_valid(train_dataloader, valid_dataloader, model, loss, trainer, ctx, nepochs,

penal_coeff=penal_coeff, clip=clip, class_weight=class_weight, loss_name=loss_name)

epoch 1, batch 400, batch_train_loss 2.4065, batch_train_acc 0.500

epoch 1, batch 800, batch_train_loss 3.7041, batch_train_acc 0.375

epoch 1, batch 1200, batch_train_loss 3.4845, batch_train_acc 0.500

epoch 1, batch 1600, batch_train_loss 2.3639, batch_train_acc 0.625

epoch 1, batch 2000, batch_train_loss 2.0768, batch_train_acc 0.688

epoch 1, batch 2400, batch_train_loss 1.8680, batch_train_acc 0.688

epoch 1, batch 2800, batch_train_loss 3.2283, batch_train_acc 0.391

epoch 1, learning_rate 0.00100

train_loss 2.7199, acc_train 0.556, F1_train 0.567,

valid_loss 2.3674, acc_valid 0.601, F1_valid 0.611,

time 165.85 sec

****************************************************************************************************

epoch 2, batch 400, batch_train_loss 3.1598, batch_train_acc 0.406

epoch 2, batch 800, batch_train_loss 2.5149, batch_train_acc 0.562

epoch 2, batch 1200, batch_train_loss 2.5872, batch_train_acc 0.594

epoch 2, batch 1600, batch_train_loss 3.0138, batch_train_acc 0.516

epoch 2, batch 2000, batch_train_loss 2.4245, batch_train_acc 0.500

epoch 2, batch 2400, batch_train_loss 2.3006, batch_train_acc 0.594

epoch 2, batch 2800, batch_train_loss 2.9407, batch_train_acc 0.484

epoch 2, learning_rate 0.00100

train_loss 2.3765, acc_train 0.607, F1_train 0.617,

valid_loss 2.3342, acc_valid 0.632, F1_valid 0.627,

time 179.03 sec

****************************************************************************************************

epoch 3, batch 400, batch_train_loss 2.5824, batch_train_acc 0.656

epoch 3, batch 800, batch_train_loss 2.4315, batch_train_acc 0.703

epoch 3, batch 1200, batch_train_loss 2.0573, batch_train_acc 0.688

epoch 3, batch 1600, batch_train_loss 1.3279, batch_train_acc 0.750

epoch 3, batch 2000, batch_train_loss 2.9859, batch_train_acc 0.656

epoch 3, batch 2400, batch_train_loss 2.7097, batch_train_acc 0.609

epoch 3, batch 2800, batch_train_loss 2.4217, batch_train_acc 0.672

epoch 3, learning_rate 0.00090

train_loss 2.2627, acc_train 0.627, F1_train 0.637,

valid_loss 2.2181, acc_valid 0.653, F1_valid 0.659,

time 181.68 sec

****************************************************************************************************

epoch 4, batch 400, batch_train_loss 2.2029, batch_train_acc 0.562

epoch 4, batch 800, batch_train_loss 1.5384, batch_train_acc 0.738

epoch 4, batch 1200, batch_train_loss 2.6499, batch_train_acc 0.578

epoch 4, batch 1600, batch_train_loss 2.2700, batch_train_acc 0.594

epoch 4, batch 2000, batch_train_loss 2.2882, batch_train_acc 0.672

epoch 4, batch 2400, batch_train_loss 1.9323, batch_train_acc 0.797

epoch 4, batch 2800, batch_train_loss 1.6440, batch_train_acc 0.578

epoch 4, learning_rate 0.00090

train_loss 2.1606, acc_train 0.642, F1_train 0.652,

valid_loss 2.1590, acc_valid 0.652, F1_valid 0.657,

time 182.00 sec

****************************************************************************************************

Predictions and sampling using our model¶

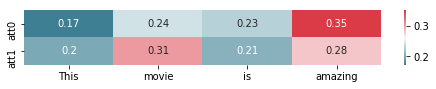

Now that the model has been trained, we can randomly input a sentence into the model and predict its emotional value tag. The range of emotional markers (or the labels) is one through five, each corresponding to the degree of negativity to positivity.

In [15]:

input_ar = nd.array(vocab[['This', 'movie', 'is', 'amazing']], ctx=ctx).reshape((1, -1))

pred, att = model(input_ar)

label = np.argmax(nd.softmax(pred, axis=1).asnumpy(), axis=1) + 1

print(label)

print(att)

[5]

[[[0.17201287 0.2443114 0.23154521 0.3521305 ]

[0.20264995 0.3056242 0.20810567 0.2836202 ]]]

<NDArray 1x2x4 @gpu(0)>

In order to intuitively understand the role of the attention mechanism,

we visualize the output of the model’s attention on the predicted

samples using the matplotlib and seaborn modules.

In [16]:

# Visualizing the attention layer

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

%matplotlib inline

np.squeeze(att.asnumpy(), 0).shape

plt.figure(figsize=(8,1))

cmap = sns.diverging_palette(220, 10, as_cmap=True)

sns.heatmap(np.squeeze(att.asnumpy(), 0), cmap=cmap, annot=True,

xticklabels=['This', 'movie', 'is', 'amazing'], yticklabels=['att0', 'att1'])

plt.show()

Conclusions¶

Word embedding can effectively represent the semantic similarity between words, which allows for many breakthroughs in complex natural language processing tasks. Attention mechanisms can intuitively grasp the important semantic features in the sentence. The LSTM captures the word-order relationship between words in a sentence. Through a combination of these three, word embeddings, LSTMs, and attention mechanisms, we can effectively represent the semantics of a sentence and apply it to many practical tasks.

GluonNLP provides us with an efficient and convenient toolbox to help us experiment quickly. This greatly simplifies the tedious work of many natural language processing tasks.